Down at the Men in Media Business Conference

A bad week for media. Plus: Lana del Rey.

Last week, Medium, the beleaguered blogging platform founded in 2013 by Twitter and Blogger co-founder Evan Williams, essentially fired their entire editorial staff. Medium started its own publications in 2019, and, not seeing its audiences grow the way it would like, is now shifting its strategy to chase after independent writers (where'd they get that idea?). Existing editorial staff were offered buyouts—more consideration than editorial staff usually get—but it was made clear that the publications these employees spent the last two years building were now dead in the startup waters.¹

Only a day after the Medium pivot, MEL Magazine announced that it was shutting down. Founded in 2015 by Dollar Shave Club—and, coincidentally, hosted on Medium until it transitioned to its own website in 2018—MEL is a men’s magazine for the internet age with some genuinely great writing, despite it being owned by a company that sends men’s razors through the mail. The fact that MEL never ran advertising, for its owner or other brands, and, up until very recently, never charged anything, meant that its existence, tucked away under the marketing budget for a multi-billion dollar company, was always tenuous. While shocking, MEL's demise is not surprising.

These two stories come in the middle of a firestorm around Substack, the newsletter platform where Night Water, among many other newsletters, is hosted. Launched in 2018, Substack is a simple and elegant way for writers to start email-based publications and charge for them. Many people see Substack as the future of media, a way for writers to build their own businesses and make more money from their writing than they could from freelancing or even a full-time gig (which are fast disappearing; see above).

Like many platforms, Substack hosts a wide variety of individuals, many of whom disagree with each other, and some of which are racist and/or transphobic assholes. Jude Ellison Sady Doyle has a good breakdown of some of the worst folks, but in short, “[Substack has] become the preferred platform for men who can’t work in diverse environments without getting calls from HR." Substack also hosts people like Jesse Singal, who has come under fire multiple times for transphobic stories, and Graham Lineham, who has already been banned from Twitter for transphobic tweets.

The main issue is that Substack chose to give some of those people money as part of a program called Substack Pro. The Substack Pro program gives writers a sizable advance to start a Substack publication, in exchange for Substack taking a higher percentage of the subscription income for the first year.

The fact that Substack seems to be directly courting writers who have expressed hateful ideologies is naturally upsetting. As writer Emily VanDerWerff puts it:

I do not mind sharing a platform with people whose views I harshly disagree with. I’m on Twitter, after all. I do not like the thought of the money my subscribers pay me being used to subsidize those people to be on this site when so many other writers whose voices actually need amplification remain in a financial bind.

Substack wants us to treat them like a platform, similar to Facebook or Twitter. As a platform, they can choose to moderate content relatively loosely and be judged for those decisions accordingly (not unlike Facebook and Twitter—after years of criticism, they have taken a heavier hand in moderating content). The fact that they are actively paying for some of that content changes things, turning Substack into a publisher. As a publisher, they can and should be held directly responsible for every word that they publish, or at bare minimum, pay for.²

But Substack wants to have its cake and eat it, too. It wants all the benefits of being a publisher—paying writers and profiting off of their work—without any of the responsibility. This is, fundamentally, unfair. What makes it even worse is that Substack won’t even tell people which writers are a part of the Substack Pro program, asking us to take their word for it that they’ve hired a diverse group of writers, and forcing us to assume that all of the worst offenders on the site have been paid in advance. It’s an absurd situation—imagine opening a magazine and not knowing which articles were written by folks paid by the publication and which were by someone who just happened to be by the printing press that day.

The major difference is that Substack publications are relatively siloed from each other—unlike Twitter and Facebook, my posts are not going to be randomly mixed with Jesse Singal’s based on an algorithm—but they are all related by money. Writers on Substack who charge for subscriptions are now asking themselves what, exactly, the 10% fee on their earnings that they give to Substack is paying for. Is it going towards the hosting fees? Or is it instead funding editorial decisions that they don’t agree with?

My livelihood is not dependent on subscription revenue or freelance writing, but since Night Water is hosted on Substack, it felt important to engage with these issues and share more information about the ongoing controversy surrounding the platform, even if it is just to my small following of family and friends. Many writers are leaving Substack for other platforms or owned-and-operated sites, while others are staying and hoping to enact change through protest and criticism. I’m in the latter camp at the moment—since I don’t charge money for subscriptions, I consider myself a drain on Substack’s resources—but I sympathize with those leaving, burned yet again by a platform choosing profit over people, and spreading hate under the guise of “free speech” when what they really want is to line their pockets.

It’s especially a bummer for all this to go down in a bad week for the media at large. Substack’s model is a genuinely exciting way for individual writers to make money on the internet, but now it seems less like the future of media and more like the same old story. As writer Brian Feldman put it in his own Substack newsletter:

For a company that wants to build its reputations on letting anyone build a stable independent business online, it sure seems like the people benefiting the most from Substack's efforts are the ones who need it the least. This is not a new phenomenon. The history of trying to make money on the internet has shown that the efforts are binary: you either rake in more money than you know what to do with, or you don't even earn enough to sustain the full-time effort. This is true of almost every platform. There is no middle class on the internet, and that seems to include Substack.

Speaking of problematic figures, last week I listened to a lot of “White Dress,” the opening track off of Lana Del Rey’s sixth and latest album, Chemtrails Over the Country Club. It's a good-enough record, with Lana intentionally dialing it back a bit after her 2019 masterpiece Norman Fucking Rockwell!

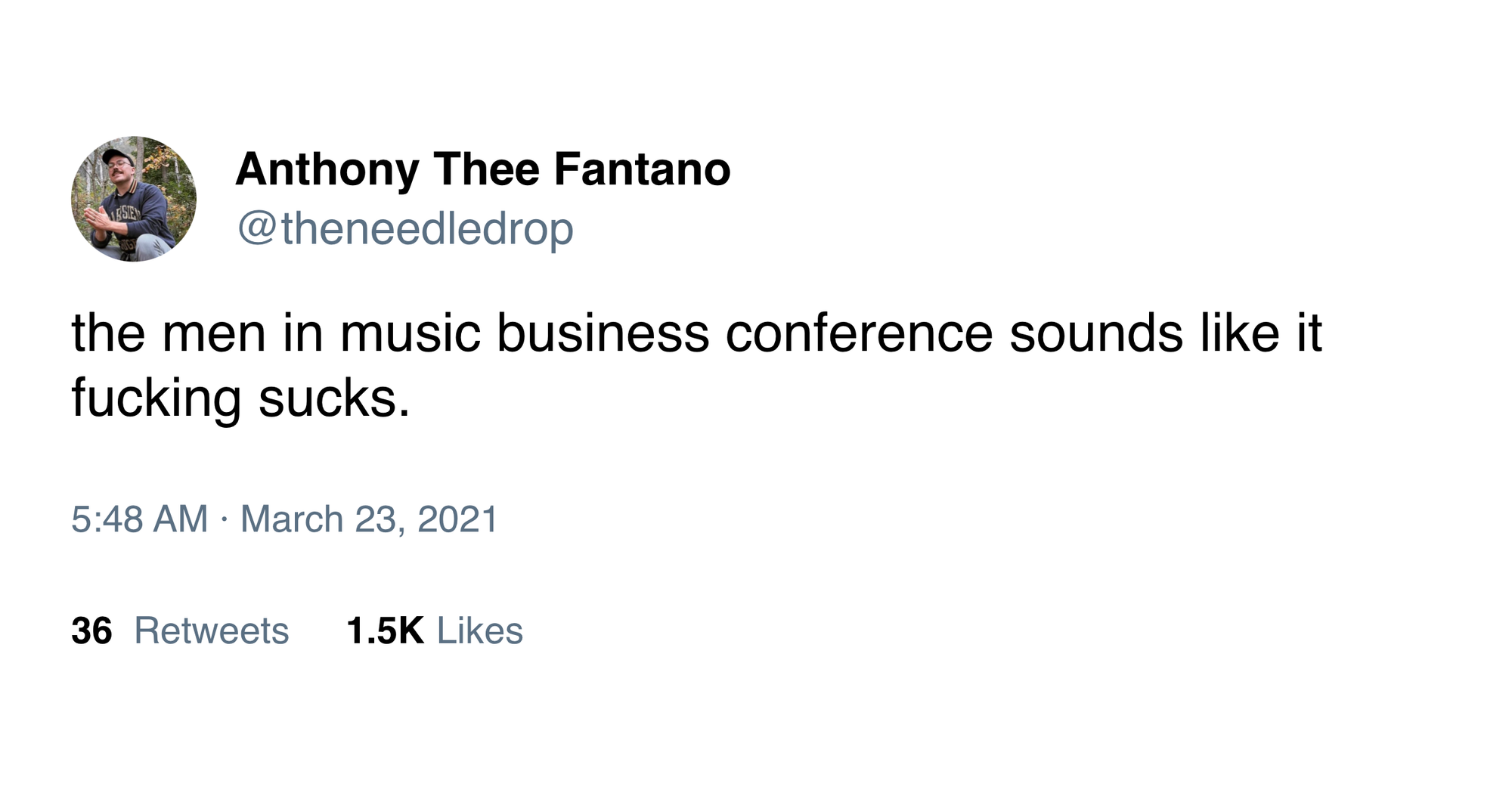

“White Dress," though, is a fucking banger. I listen to it over and over again just to hear Lana half-whisper way too many syllables in the line “Down at the Men in Music Business Conference.” It’s a fantastic line, not least of which for the memes and tweets it inspired:

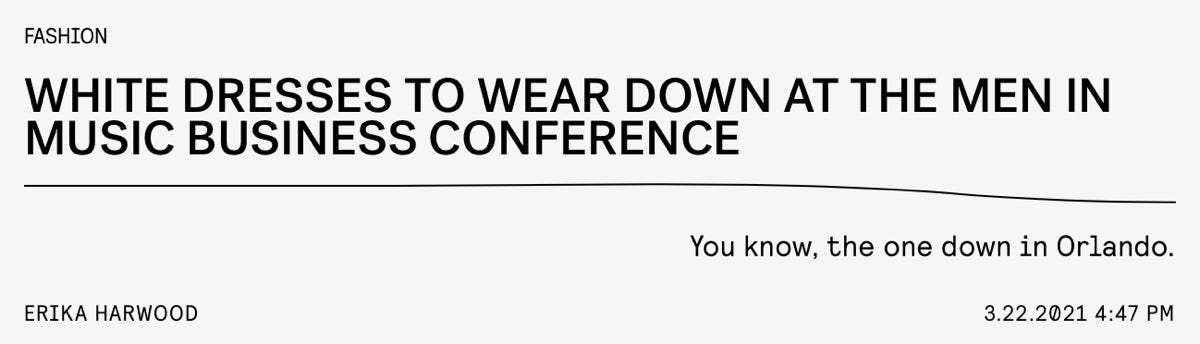

I also just want to congratulate Nylon on just an absolutely perfect piece of affiliate content:

The future of media is referential content that primarily serves to sell random shit on the internet, and I am here for it.

I applied for a job at Medium in 2016, completely bombed the interview, and then, just a few months later, Medium shut down their entire New York office. Presumably, these events are unrelated. ↩

Think of the New York Times, for example—after Senator Tom Cotton's horrific and unconstitutional op-ed last summer calling for Trump to send troops to quell Black Lives Matter protests, opinion editor James Bennet resigned. ↩