Star Wars should be in the public domain

Star Wars is part of the fabric of our culture. Why should one company get to control it?

Tomorrow is Star Wars Day, a fake holiday created by the Star Wars fandom to celebrate the franchise. Disney, owners of Lucasfilm and the Star Wars franchise since 2012, have embraced the holiday, and since used it as a chance to announce upcoming film and TV projects, launch new merchandise, and generally attempt to control the narrative around all things Star Wars.

Around the time that the second Disney Star Wars movie, The Last Jedi, came out, there was a tweet going around that called on Star Wars fans to collectively raise $4 billion to buy Lucasfilm from Disney. The Last Jedi was and continues to be polarizing among fans for a variety of reasons—from complaints about it being too “woke” to folks who found it to be anti-climatic wheel turning. This guy was calling on the fandom to take back the wheel from Disney and right the ship.

I remember him getting dunked on pretty hard—one, for his naivety in thinking that Disney would willingly sell Lucasfilm for the exact amount it paid for it, and two, for thinking that all of those Star Wars fans would actually agree about the way forward for the franchise. But I think he had a point—Star Wars is important to a lot of people. It has, for better or worse, become part of the fabric of our culture. Why should one company, a company that also owns a ton of other contemporary characters and stories, get to control it?

In the olden days, they wouldn’t—copyright protections were limited to a much shorter period, allowing work to enter into the public domain. When something is in the public domain, anyone can make new work based on it. Think Greek myths or Shakespeare or 19th-century novels—or any of the fairy tales that Disney adapted when forging its animation empire in the 1930s. Those characters don’t belong to anyone, ergo, they belong to all of us.

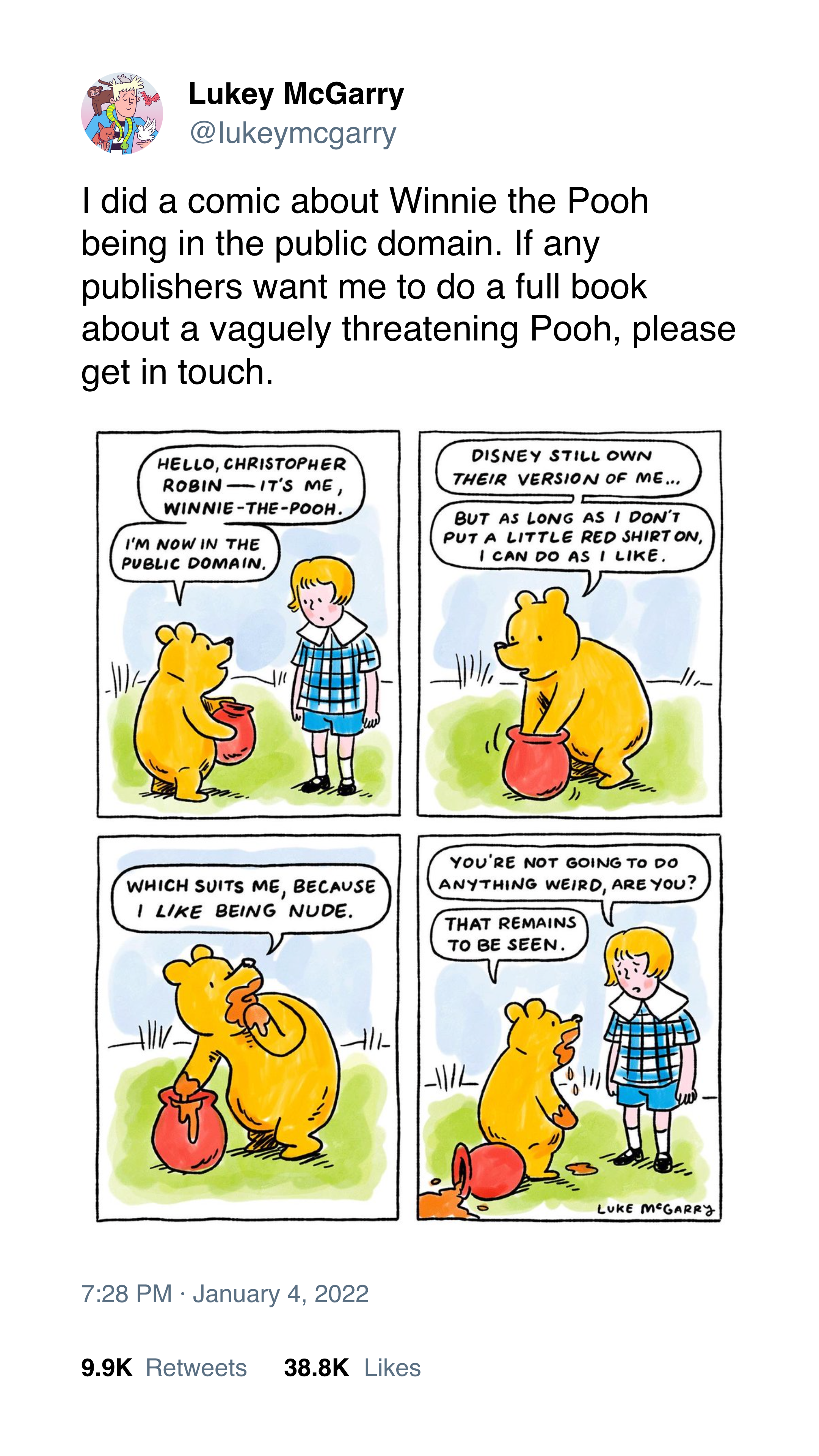

This year, hundreds of thousands of works from 1926 entered the public domain¹, including the first Winnie-the-Pooh book and works from Hemingway, Agatha Christie, and Langston Hughes. But, as Jennifer Jenkins, Director of Duke’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain, notes:

…under the laws that were in effect until 1978, thousands of works from 1965 would be entering the public domain this year. In fact, since copyright used to come in renewable terms of 28 years, and 85% of authors did not renew, 85% of the works from 1993 might be entering the public domain! Imagine what the great libraries of the world—or just internet hobbyists—could do: digitizing those holdings, making them available for education and research, for pleasure and for creative reuse.

The original Star Wars film came out in 1977. Based on current copyright laws, it will enter the public domain 95 years after publication, or 2072. A good portion of you reading this will be dead by then!

Allowing copyright to expire creates a wellspring of creativity, letting a new generation build on the works of the past and continuing the cycle of storytelling that defines human civilization. While there is an obvious economic benefit to copyright protection—it provides an incentive to create the work in the first place—there is also an economic benefit in expanding the public domain and inspiring new work. Plus, there are untold benefits for communities and individuals who can now screen films, put on plays, or perform music from the public domain without having to pay a license fee, plus all the benefits for researchers and archivists who can work to preserve and distribute older works, especially when it no longer becomes financially advantageous for a commercial company to do so. When copyright is extended, entire generations miss out on these benefits.

Amazingly, copyright lengths in the United States have been extended twice since the first Star Wars movie was released. In large part, these 20th-century copyright extensions are a direct result of Disney’s lobbying to keep Steamboat Willy, the first Mickey Mouse short, from falling into the public domain. With Steamboat Willy’s copyright now set to expire on January 1, 2024, will we see lobbying from Disney in the coming year to extend copyright lengths even further? Does the fact that Disney let the first Winnie-the-Pooh book slide into the public domain suggest that their quest for infinite corporate copyright has come to an end?

The reality is that the original copyright probably won't have to be extended in order for Disney to maintain control over their Winnie the Pooh franchise (they dropped the hyphens) or Mickey Mouse. New work with those characters creates a new copyright, specifically for the newly added material, which can make it less clear what is in the public domain and what isn't. Disney's version of Pooh, a stout yellow bear with a red crop top, is distinct and protected for another four decades. So is the modern version of Mickey. Trademarks can also make things complicated—while the Supreme Court has ruled that trademarks can't be used to extend copyright protections, Disney can still use their money and lawyers to scare creators away from using trademarked characters.

Disney's market power is more reliant on its control over copyrighted material than ever. As Matt Stoller, author of Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy and writer of the newsletter BIG, puts it, “the new Disney is more a private equity group than studio, collecting brands and using them to bargain aggressively with partners, suppliers and consumers.” This consolidated control over their original animated and live-action films, Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm, and 20th Century Fox is already having major effects on the entertainment industry. Disney films account for around 30% of all domestic movie tickets sold, more than any other studio. This allows them to extract onerous terms out of movie theaters, such as demanding higher percentages of the box office and forcing theaters to show Disney films in their biggest theaters. Theater chains, already struggling, have no choice but to comply in order to get access to this must-have content. Additionally, Disney has been cutting off access to the back catalog of 20th Century Fox—classic films that small, independent theaters often rely on showing to stay profitable. For those of us who love seeing movies in theaters, Disney is enemy #1, turning theater chains into another arm of their empire and crushing any independent theaters they cannot exploit.

In his article "Copyright, Antitrust, and Disney's Monopoly," Stoller describes how Disney has used its control over "must-have" content to muscle its way into the streaming wars. Stoller doesn't think that copyright term lengths are the issue here—he proposes antitrust measures that would break up vertical integration between producers and distributors—but I disagree. The lynchpin of Disney's power comes from control over popular characters and fictional universes. Sure, you could force them to license their work to other streamers. Or you could take away their copyright and allow anyone to freely distribute that content, or make a Star Wars movie, or a Marvel TV show, or an Alien prequel.

Let's say we rolled things back to the 1909 law, and copyright was capped at 56 years. Disney's animated classics would be freed from the vault. Most of the current popular Marvel characters, such as Spider-Man, Doctor Strange, Scarlet Witch, and the entire concept of The Avengers would enter the public domain. We'd still have to wait a few more years for Star Wars—I couldn't make my Luke Skywalker/Han Solo rom-com until 2033—but it would take a big swipe out of Disney's pop culture dominance. Not quite the Rebels blowing up the Death Star, but maybe something like taking out a hemisphere.

A rollback of copyright term lengths is highly unlikely—an unsuccessful challenge to the 1998 extension made it all the way to the Supreme Court in 2003, and Congress won’t do anything that puts us out of whack with international trade agreements. But as you're seeing the stream of news come in from Star Wars Day, watching Disney expand their streaming, theme park, and merchandise empires, you can imagine another world, one where a child who was captivated by the first Star Wars in theaters could grow up to someday make their own Star Wars movie, whether Disney wanted them to or not.

At least in the U.S.—your mileage may vary with international copyright and public domain, though thanks to trade agreements, more countries are adopting longer copyright terms. ↩