Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M.

guest post by Mathilda Hallstrom

Today’s Night Water—arriving in your inbox on Wednesday morning at 3 a.m. eastern—is a guest post from writer Mathilda Hallstrom on Simon & Garfunkel’s debut record. You can find more from Mathilda at her newsletter, All The Right Notes.

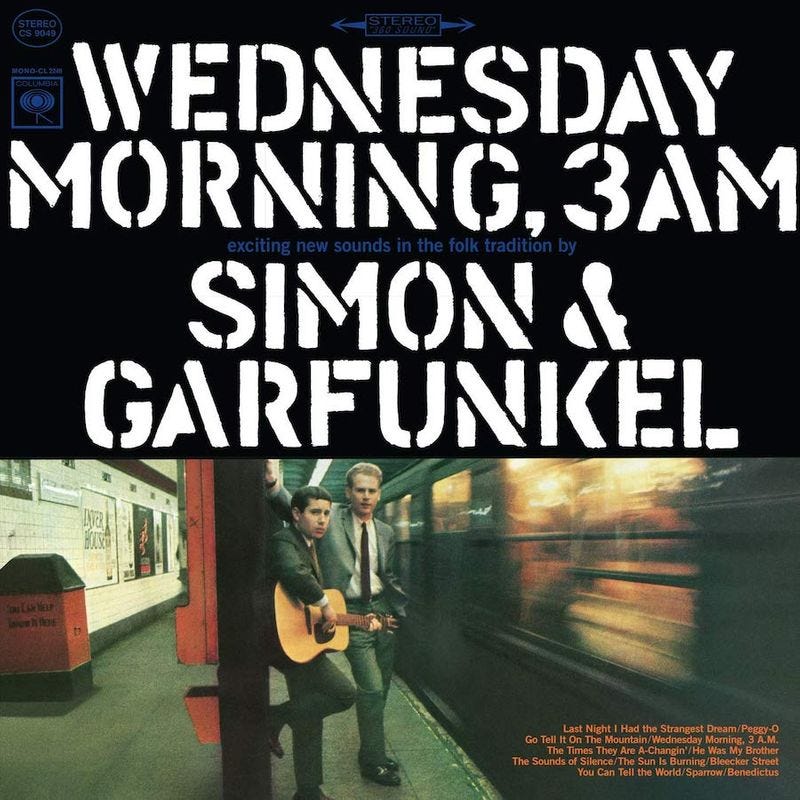

It began, as all great friendships do, at Public School 164 in Kew Gardens Hills, Queens. Eleven-year-olds Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel first encountered each other at their school’s sixth-grade production of Alice in Wonderland, learning that they lived only three blocks away from each other. Three years later, the duo wrote their first song together; eight years after that, they released their first album, Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M.

Standing side-by-side, suited-and-tied on the lower subway platform at 5th Avenue and 53rd Street in New York City, the young Simon & Garfunkel promise “exciting new sounds in the folk tradition…”. Produced by Tom Wilson, the twelve tracks of Wednesday Morning include a late-Renaissance Latin text, a strummed sea shanty, and an ode to a victim of the Freedom Summer Murders—a great definition of exciting in 1964.

At the time, Simon was a student at Brooklyn Law School and Garfunkel a student of art history at Columbia University. The two had performed under various billings through the years—Tom & Jerry, Kane & Garr, and, briefly, Simon as True Taylor—but, upon Simon’s insistence, released their debut under their own names.

Upon its release, Wednesday Morning sold a mere 3,000 copies. Billboard chart records indicate that, at the time, America wasn’t particularly excited about folk: the softer acoustic qualities of Simon & Garfunkel’s first album were less compelling than the fuller, faster sounds of the Beatles’ Rubber Soul. But at the time, the seed of folk-rock had already been planted in Simon & Garfunkel’s native New York City, particularly in Greenwich Village, where their contemporaries were playing gigs and hosting hootenannies in bars across the neighborhood. Surrounded by other folk legends like Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez, and Bob Dylan, the duo was squarely positioned in the capital of the folk revival.

Nearly sixty years later, now that we’ve had time to process the Beatles, Wednesday Morning 3 A.M. deserves a reevaluation. Simon & Garfunkel’s debut effectively indicates the intimate, touching songwriting and crisp production that would eventually immortalize them as one of the most beloved duos in history. Due to these tender qualities, the album lives up to its name—its acoustic, gentle nature fits the witching hour vibe beautifully. I’d give it a spin at 3 A.M. myself, but I can’t stay up that late.

“The Sound of Silence”, perhaps the best-known track found in Wednesday Morning, has taken on a life of its own in recent years but poses the strongest indication of the duo’s songwriting chops. Written by Simon in the aftermath of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the song reportedly earned the duo their record deal at Columbia, having performed it during a studio audition. The song only gained traction with the public upon its remixed re-release a year later, orchestrated by in-house producer Tom Wilson, who supplemented the song with a crashing folk-rock beat. Its remix retains the track’s sheer emotionality but provides a powerful lift and momentum to Simon’s lyrics; the despair and questioning expressed within are given more of a vehicle to propel itself forward. But even without a drum track, “The Sound of Silence” best illustrates the literary aptitude the duo came to display in their later work, evoking intimate perspective-based imagery and brushing the surface of culturally shared anxieties of the time. If Simon & Garfunkel can do anything, they can make existential crisis sound beautiful.

“Bleecker Street”, also written by Simon, employs similar compositional techniques, illustrating a stroll down the titular street in Manhattan. In “Bleecker Street”, Simon weaves the general social misgivings he expresses throughout the album into a more personal experience: he watches fog “[fill] the alleys where the men sleep” and hears “voices leaking from a sad cafe.” The song identifies a mutual sadness creeping its way down the street, a sense of having wavered from one’s values somewhere along the way: “It’s a long road to Canaan / on Bleecker Street.”

The album concludes with its titular track, detailing the inner monologue of a petty criminal who watches his love sleep as he realizes he’ll be separated from her in due time: “She is soft, she is warm, but my heart remains heavy / and I watch as her breasts gently rise, gently fall / for I know with the first light of dawn I’ll be leaving / and tonight will be all I have left to recall.” The song, although narratively sparse, is impactful merely through its soft, sweet composition and loving descriptions. While its musical qualities bring some levity to the story, you can hear the grief in Simon’s performance; the story is fictional, but the loss feels real.

Few of Wednesday Morning’s songs are original compositions: the album opens with the gospel song “You Can Tell the World” and also features covers of “Go Tell It on the Mountain”, “Peggy-O”, and Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are a-Changin’.” In my opinion, the inclusion of these covers is what makes the album sound so classic — Simon & Garfunkel are paying tribute to the traditional tunes that came before them and will last long after they’re gone. These are songs that speak to values and morality—love, faith, perseverance—the very values that Simon laments the loss of in “Bleecker Street.” Wednesday Morning attempts in many ways to reckon with the cultural and political climate of the time, and one of those ways is, perhaps, removing time entirely.

Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M. isn’t the best of what Simon & Garfunkel have to offer, but it sets the stage for decades of renowned songwriting and folk classics. Its compositions aren’t particularly inventive, but no less pleasing for it; its performances are expertly intimate and, at times, quite powerful. These sixty years later, it’s clear that Simon & Garfunkel got off on a good foot.

The feeling of shared social crisis—the notion that somewhere, somehow, something went wrong—isn’t new now, and it wasn’t new in 1964. The sentiment of society’s loss of values and misdirection is one of the most consistent across time; it’s been lamented through nearly every social movement and reflected in nearly every culture in our world. It’s a feeling I understand well myself: I’m about the age Simon & Garfunkel were during the production of Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M., and it strikes a nerve. The specific qualities of our anxieties might be different—mine are more focused on insurmountable student debt and the current cost of living—but the sentiment is there, always underlying, always creeping. There’s a sense of abandonment implied, like whatever force that brought us to this earth has left us to our own devices, and we’re not doing very well without it.

In the face of all this fear, I’ve seen a lot of people turn to the nearest defense mechanism: irony. When everything is overwhelming, whether it be internal or external, it’s much more simple to shut down the part of you that feels, the part of you that takes a good, clean look around and accepts things as they really are. Humans have always used humor to deal with the uncomfortable, but it feels like the developing youth of today have turned away from sincerity entirely. Every generation is selfish and blind and foolish in their own right—it seems that my own is hesitant to take things seriously.

I’m working on executing the exact opposite in my own life. I want to feel everything, to acknowledge everything, no matter how much easier it would be to retreat to the ironic repartee I’ve grown accustomed to. Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M. is bursting at the seams with sincerity: Simon & Garfunkel want to talk about the world around them, the bad and the good and the questionable, and reflect their own values and experiences in traditional song.

Sixty years later, we can learn something from this sincerity. We can still heal from the parts of us that don’t know how to regard the world without a protective layer, we can relate, we can lament what we’ve lost. And if you ask me, listening to Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M. is a great way to get started.